27 Jul 2009

The following post is an unedited essay I prepared for a subject on globalisation and China last semester, and investigates the role of the Internet particularly as an instrument of social change. Perhaps surprisingly, I argue that it is a reflective, rather than disruptive, utility in this particular social context.

The new technologies will bring “every individual … into immediate and effortless communication with every other,†“practically obliterate†political geography, and make free trade universal. Thanks to technological advance, “there [are] no longer any foreigners,†and we can look forward to “the gradual adoption of a common languageâ€.

—1893 article

Communication technologies have long been perceived as harbingers of significant transformation in society, from the tumult of 15th C. Europe in the wake of religious and political revolution enabled by Gutenberg’s invention to the domestic telegraphic and telephonic innovations of the 1800s. As boundaries between countries have, with increased access to Information and Communications Technology (ICT) beyond the elite, begun to blur, proletarian access to such technologies has commensurately grown apace. Despite common access to such technologies, however, their utility for grassroots activism, the devolution of state boundaries, developing global commerce, and advancing political autonomy remains in question. Considering China, particularly, with over one-fifth of its population having access to such technologies based on official estimates, the question of the utility of these technologies, particularly in the realm of their impact upon the social and political psyche of China, is an important one.

Most commonly levelled critiques against the Chinese Government in the field of Internet politics gravitate around the issue of Internet censorship. In a global context, this has ramifications for a variety of organisations, both TNC/MNCs and governments. The Golden Shield Project (金盾工程), it is often argued, is both facilitated by the complicity of and provides benefit to a variety of ICT vendors in western democracies. In the United States particularly, vendors including Cisco Networks, Microsoft and service providers Google and Yahoo! have all been dragged before various inquiries into the foreign practices of the global subsidiaries and branches of such businesses. Although various US export restrictions on some security products (high grade encryption being foremost amongst these) remain, export constraints apply principally to countries with which the US does not have diplomatic relations or where it is presently engaged in military conflict. China fits neither criteria, and her internet practices, although considered oppressive by some, do not even depend particularly upon any advanced encryption technologies: indeed, such technologies are often used for the circumvention of controls.

For all its faults, control of the Chinese internet is an imprecise science, exemplified in former-US President Clinton’s description of such attempts as like “trying to nail Jello to a wallâ€. Other media, limited by a raft of controls imposed by the State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (SARFT) and the General Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP), are particularly controllable in a manner the Internet is not. While both SARFT and GAPP have attempted to assert control over the Internet in a variety of forms, GAPP’s online authority is limited in scope compared to the tight control it retains over periodicals and book publishing through ISSN/ISBN issuance, while SARFT’s March 30 notice, â€œå¹¿ç”µæ€»å±€å…³äºŽåŠ å¼ºäº’è”网视å¬èŠ‚目内容管ç†çš„通知â€, is concerned only with ‘audio-visual programs’ published through Chinese video sharing websites. While the SARFT notice singles out videos published by æ‹å®¢ (‘vodcaster’, or video netizen reporter), it does not target bloggers or any non-visual reporting. Particularly the permit system in part 4 of the notice, essentially an extension of existing SARFT regulations over film/TV serialised content, raised the ire of a number of video-on-demand websites. For the average user, however, this appears to have had little impact. While various administrations may attempt to challenge or even change the nature of Internet interactions, the Internet shows equal resilience and, indeed, presents an inverse challenge to such established bodies. Despite this, however, the prolonged censorship of the internet under the direction of the Ministry of Public Security’s Golden Shield Project, particularly in conjunction with various MIIT directives to service providers, has resulted in what is effectively a culture of self-censorship of the Chinese Internet.

However, there are many issues, often neglected in the wake of clamorous discussion surrounding the censorship issue, besides that of access. Particularly, when considering the Internet as an instrument for disrupting the official discourse and challenging or transforming societal conventions, it is important to consider usage patterns in online activities. China is predominantly interested in very different activities to a wider sample of the online community. While considering the issue of utility, it is worth noting that the top Internet applications in China, namely Music, News and Instant Messaging (IM) activities, constitute entertainment related pursuits, as opposed to more commercially motivated Internet activities of much of the rest of the world.

This usage disparity is reflective of other consumer attitudes within China. It does not shape them. The dependence of global online commerce upon a consumer-credit based systems, specifically, third party brokers with broad networks and the capacity to instantaneously authorise and/or decline transactions based on verification of available credit (in Mainland PRC, the only domestic interbank network facilitating this is China UnionPay (ä¸å›½éŠ€è”), though affiliations with global VISA and MasterCard networks of course persist), is obviously problematic in a country that has only begun to embrace credit systems, with high saving rates. Accordingly, services such as AliPay have emerged, with agreements spanning existing banking institutions as well as larger existing credit networks, UnionPay and the global VISA/MC networks amongst these, in order to facilitate trust-based internet transactions.

The emergence of such institutions is a recent development in Chinese society. As Nie Jin observes in a 2007 paper concerning current e-payment solutions in China, one of the virtues of a centrally planned economy prohibiting individual and private transactions is that there is no need for any trust/credibility system to enable such transactions. As these have emerged in the wake of economic reform, so too has demand for escrow and trust-based transaction services developed. The paper continues to note that, outside of China and planned economy states, accrued data suggests as much as 90% of business transactions are settled on the basis of integrity (i.e. without resorting to third party escrow services, etc., though possibly involving a payment network mediator without a trust layer).

In this, the Internet functions not as an instrument acting upon China to change it, but merely another manifestation of an already-changing economic reality. As private enterprise grows, it is logical to pursue the Internet as yet another sales and/or marketing channel, and, in doing so, the same issues already identified will be faced regarding trust online as in person. There are of course particular challenges to online business (fraud/verification of identity, logistics/delivery, etc.), but at the level of changing social landscapes it is clear the most pressing issue, that of integrity, is derived not from the emergence of a distributed, globally inter-connected network of prospective clients and vendors, but rather as a result of economic reforms implemented over the course of thirty years.

What, then, of transactions that transcend national borders and geographic boundaries? Traditionally China’s largest trading partners have consisted of Asian neighbours whose socio-cultural and personal ties commend them as such. In an era of global trade facilitated by buyer/seller protecting trust networks, is there any reason for this privileged trading status to continue? Of course there is. Guanxi can only account for so much: there are logical, practical reasons beyond this for barriers the Internet cannot (yet) alleviate. The so-called ‘digital divide’ is often spoken of in terms of access to technology. It is clear, however, that physical access to technology is not sufficient. Education is often addressed as an issue affecting access, but it is generally raised only at the level of computer literacy. With China rapidly embracing the Internet through both PC and mobile technologies, and particularly with the recent approval of licenses for TD-SCDMA/TD-LTE networks (3G/4G network technologies that will dramatically improve network access speeds), the issue of physical access is decreasingly relevant. Additionally, as mobile access improves and touch-capable handsets increase in prevalence, barriers to usability also decrease.

What, then, is the problem? The networks are in place, users can access them, and yet trade barriers persist. There are several issues at play here. Firstly, the dominance of the Anglophone Internet compared to English literacy in China. While China is one of the largest English-speaking countries, as a proportion of its own population this is not a dominant language, and access to much Internet media and technology requires English literacy in order to comprehend or use services. This is a contributing factor behind the adoption of social networking services such as Kaixin and Xiaonei over their antecedent equivalents in the wider Internet: Facebook particularly has offered for some time now an Chinese language version, but its failure to sufficiently localise content from the beginning (it is, by default, served in English) granted Chinese clones advantage required to capture the mainland market first.

Secondly, there are cultural barriers. China has an enviable adoption of blogging and ‘independent’ publishing technology. On CNNIC statistics, there are over 162 million blogs in China: representing half of China’s Internet population, on the assumption of only one blog per user. Yet, despite such dramatic adoption of this medium, expression is tempered by various regulations imposed upon publishers by service providers. Service providers who fail to conform to such regulations face unpredictable service denials facilitated by Golden Shield Project proxies and firewalls: Blogger and WordPress.com represent two prominent examples of such providers. Technical considerations aside, the effect of this conformity is a homogenisation of blog content that is prohibited from featuring controversial material. The video netizen reporters targeted under the March 30 SARFT directive are particularly addressed on account of the difficulty of automatically protecting against video content: scanning blog posts for banned keywords is much more achievable. Thus, this (imposed) self-censorship stymies the development of an independent Chinese blogging community within ethnic media: ironically, the dependence of dissident bloggers upon non-conformist service providers reduces the effects of their dissidence and, commensurately, their relevance and impact upon the wider Internet. The entertainment-oriented activities of Chinese Internet users are primarily consumptive in nature, and the generative activity of content creation is accordingly marginalised while so much attention continues to be paid to officially regulated media. One hundred and sixty two million bloggers can’t be silenced, but they can be (mostly) irrelevant.

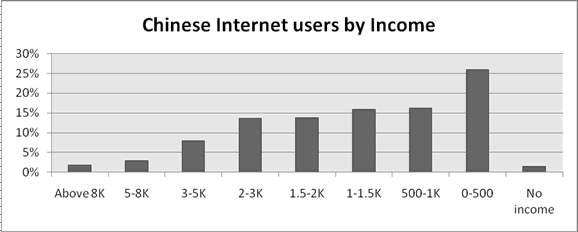

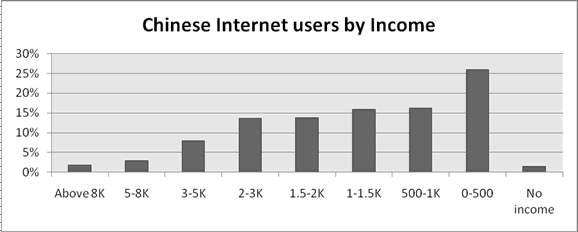

Thirdly, the economic barriers to global participation are significant. In a positive reflection upon China’s internet penetration, for the past several years CNNIC’s annual reports have identified approximately one quarter of internet users as having monthly income of less than 500 RMB.

This has an obvious impact upon the willingness of netizens to engage in financially-related online activities, as disposable income is negligible for many of them. This is borne out in another CNNIC report particularly concerned with adoption of security software (安全软件) in personal computing, particularly a section identifying individuals’ greatest concerns where computer security problems are encountered. The greatest concern is loss of computer files and any virus that will affect the operation of the computer: these two comprise over 50% of respondents’ greatest concern. Neither situation involves the theft of files, only the disabling of the user’s computer. This reflects relatively lethargic adoption of e-commerce and internet banking in China, and is not a cause of it. General consumer attitudes beyond Internet-specific security concerns represent the greatest threat to Internet-based financial services growth.

The Internet has not, here, changed China. Indeed the question of income equality is in need of resolution before the Internet can be used to any great economic effect: it certainly does not presently fulfil that role for many users. Despite these qualifications, it is undeniable that China is of advanced global standing in purchase of certain digital goods connected to digital social contexts. QQ/Tencent is one prominent example of an effective digital goods business model not really replicated with great success in the west. Similar to this in a game environment are massively multiplayer games that allow conversion of cash to in-game currency. This form of digital economy is unessential and recreational in nature. Internet development practice here is unique and at the forefront of global industry, yet it continues to reflect real-world paradigms: Nike shoes, Gucci bags, and other luxury brand items function as signs of status in the same way webpage decorations or virtual decorative armour does. Thus here, too, the Internet fulfils an emulative, rather than transformative, social role.

The Internet has been lauded and demonised as a challenger to the establishment. This is evidently the party view of the matter: its Golden Shield Project reportedly accrued 6.4BN RMB in costs in its preliminary phases, and countless more since. However, as a result of regulation and control, the Internet in China represents not a threat, but a mechanism for the effective consolidation of party power. Far from functioning as a broadly transformative social mechanism, the Internet chiefly embodies the attitudes and values of the community in which it is set. Additionally, the boundaries imposed by linguistic, cultural, hypertextual, political and technological mechanisms function in effect to produce a ‘localised’ form of the Internet. As Goldsmith and Wu note in their book Who Controls the Internet, one of the virtues of a ‘bordered Internet’ is that domestically held values and standards can be preserved in a form that permits peaceful co-existence in online contexts —certainly there must be many within the Chinese administration who have wished this to be true as issues of international diplomacy have spilt over in nationalistic fervour on BBS and forums across the Chinese Internet.

All these boundaries are, of course, fluid. This is one of the great virtues of the Internet, and one of the enabling forces that will perhaps one day enable significant change, offering more than a reflection of society. For now, however, China is captive to broader societal forces that impact upon its Internet usage. The decline of censorship does not appear imminent: media reforms in recent years have been driven largely by economics rather than social discontent. If the benefits of open information exchange eventually outweigh the CCP’s desire for control, it is likely that the framework of control established over the Internet over the past 13 years since public BBS access was first offered will persist: if ensuring a stable and ‘harmonious society’ is the goal, whatever critics may say of oppressive Internet regimes, the promotion of a culture of consumption and self‑censorship promises, at least in the short term, to reduce immediate challenges to the administration. The Chinese Internet has changed China’s attitude to the Internet, certainly, but the speculations made over 100 years ago concerning universal free trade and common language are as close to fulfilment by the Internet as by the telegraph. A globalised culture, enabled more by force of advertising and mass media than by the Internet, is driving these factors. Technology, whilst providing a channel for the expression of such culture, remains stoically neutral in imparting values and attitudes.

Hawthorne, J., “June 1993,â€

The Cosmopolitan, February 1893, 456-57, in Goldsmith, J. & Wu, T.,

Who Controls the Internet?, 2006, Oxford University Press

CNNIC, “Internet Timeline of China (2008)â€,

http://www.cnnic.cn/html/Dir/2009/05/18/5600.htm Published 18 May 2009. Accessed 4 June 2009. Proportion derived from CIA World Factbook population projections from 2000 census at 1.34BN

Drake, W.J., “Dictatorships in the Digital Ageâ€,

iMP, October 2000, in Hughes, C.R., “Controlling the Internet Architectureâ€, April 2002, in ASNS3619 reader.

国家广æ’电影电视总局, ã€Šå¹¿ç”µæ€»å±€å…³äºŽåŠ å¼ºäº’è”网视å¬èŠ‚目内容管ç†çš„通知》,

http://www.sarft.gov.cn/articles/2009/03/30/20090330171107690049.html Published 30 March 2009. Accessed 5 June 2009.

CNNIC/Pew Research Centre in Angelova, K., “Chart of the Dayâ€,

The Business Insider,

http://www.businessinsider.com/chart-of-the-day-the-chinese-get-more-entertainment-online-the-americans-shop-2009-5 Published 22 May 2009. Accessed 5 June 2009.

Nie Jin, “Analysis of Current E-Payment Solution in China-Third Party Payment Platformâ€,

First International Symposium on Data, Privacy and Eâ€Commerce, 1-3 November 2007. IEEE Xplore 10.1109/ISDPE.2007.22

Lü Yao-Huai, “Globalization and Information Ethicsâ€,

Localizing the Internet: Ethical Aspects in intercultural perspective, 2007, Paderborn.

Including in this not only state-controlled sources, but state-monitored/filtered services, such as BBS/forum services and, under the new SARFT regulations, licensed video-on-demand websites.

CNNIC, “2008å¹´ä¸å›½ç½‘æ°‘ä¿¡æ¯ç½‘ç»œå®‰å…¨çŠ¶å†µç ”ç©¶æŠ¥å‘Šâ€,

http://www.cnnic.cn/uploadfiles/pdf/2009/3/27/142455.pdf Published 27 March 2009. Accessed 4 June 2009. pp. 16

CCTV News, 3 September 2002, recorded at

http://www.epochtimes.com/gb/3/10/22/n397830p.htm Published 22 October 2003. Accessed 7 June 2009.

Bibliography

Angelova, K., “Chart of the Dayâ€, Business Insider, http://www.businessinsider.com/chart-of-the-day-the-chinese-get-more-entertainment-online-the-americans-shop-2009-5 Published 22 May 2009. Accessed 5 June 2009.

CCTV News, 3 September 2002, recorded at http://www.epochtimes.com/gb/3/10/22/n397830p.htm Published 22 October 2003. Accessed 7 June 2009.

ChinaInternetWatch.com, “China Internet Statistics 2009 Whitepaperâ€, ChinaInternetWatch.com, 13 April 2009. Accessed 4 June 2009.

CNNIC, “2008å¹´ä¸å›½ç½‘æ°‘ä¿¡æ¯ç½‘ç»œå®‰å…¨çŠ¶å†µç ”ç©¶æŠ¥å‘Šâ€, http://www.cnnic.cn/uploadfiles/pdf/2009/3/27/142455.pdf Published 27 March 2009. Accessed 4 June 2009.

CNNIC, “Internet Timeline of China (2008)â€, http://www.cnnic.cn/html/Dir/2009/05/18/5600.htm Published 18 May 2009. Accessed 4 June 2009.

Drake, W.J., “Dictatorships in the Digital Ageâ€, iMP, October 2000, in Hughes, C.R., “Controlling the Internet Architectureâ€, April 2002, in ASNS3619 reader, Dr David Bray, 2009.

Goldsmith, J. & Wu, T., Who Controls the Internet?, 2006, Oxford University Press

Lü Yao-Huai, “Globalization and Information Ethicsâ€, Localizing the Internet: Ethical Aspects in intercultural perspective, 2007, Paderborn.

Nie Jin, “Analysis of Current E-Payment Solution in China-Third Party Payment Platformâ€, First International Symposium on Data, Privacy and Eâ€Commerce, 1-3 November 2007. IEEE Xplore 10.1109/ISDPE.2007.22

国家广æ’电影电视总局, ã€Šå¹¿ç”µæ€»å±€å…³äºŽåŠ å¼ºäº’è”网视å¬èŠ‚目内容管ç†çš„通知》, http://www.sarft.gov.cn/articles/2009/03/30/20090330171107690049.html Published 30 March 2009. Accessed 5 June 2009.

25 Jul 2009

(East) Africa just had their global Internet connectivity significantly expanded. Education applications are presently limited to the tertiary sector. However, the promise of growth in Kenya and Tanzania particularly is significant as costs fall. Initially ISPs in this region have gone for higher bandwidth over cost reduction. That said, if Internet access developments follow models established already in China and India, conventional ISPs aren’t going to deliver growth, mobile providers will.

Accordingly, the improved bandwidth situation at the present prohibitively expensive costs of ~$600/month for a good link is ultimately a bit irrelevant if mobile tech delivers last-mile infrastructure and the mobile web enables e-commerce, social media participation, governance, healthcare and more. This isn’t a case for existing ISPs to drop prices: they’ve definitely got a very good business case for leaving prices up but using the link to improve value while this is still a valuable commodity. The only significant short-term challenge to this comes, potentially, in the form of any government policy implemented. They might do well to intervene here and stimulate economic development by promoting global connectivity… but I suspect the interests of established business and government, if they resemble anything like those in Australia, coincide too significantly for such bold maneuvers to ever come to fruition!

From a business standpoint, it makes sense to capture these markets with medium bandwidth technologies early. That said, the relatively limited capacity of this additional global link makes co-location essential for any serious engagement. What this represents is an important in-road for low-outlay development of new markets with significant parallels to existing products (i.e. to English-speaking populations without need for additional infrastructure).

For East Africans, however, this is much bigger. Internet connectivity enables exports of innovative solutions, and, as social media uptake improves, of localised (l10n)/internationalised (i18n) solutions in response to this newly-visible Internet market segment. The problem of ghettoisation along language lines is not so prominent perhaps as a result of significant Anglophone influence — Francophone Africa will, of course, engage in different networks because of language barriers. Yet some services, Twitter perhaps eminent among them, have irrationally succeeded independently of ‘native’ language (it remains at present offered only in English and Japanese, despite significant Chinese membership, and, who can forget, Iranian political application!) — while others (Facebook, to pick a similar example) have languished and been replaced by clones despite their linguistic plurality (26 unique languages last I recall hearing a count, including English (Pirate) and many more serious ones) — Xiaonei being but one example of this.

If language is not an issue, it is possible other disparities will become divisive in the same way. Developmental barriers in terms of software industry (a key driver of domestic web innovation) and global trading partners will steer usage in any number of particular directions. For example, China’s inept attempts at achieving independence from Microsoft software in the last decade have been effectively squashed by their rampant piracy situation. Parts of eastern Africa engage in literal acts of piracy, but it’s probably not indicative of an attitude towards or developed industry against protection of intellectual property. If the criminal distribution network doesn’t yet exist, and software adoption is insufficiently mature, it’s entirely possible that open source could win. This is naive, and based on the presumption that Africa has, to date, existed in a vacuum — but if we consider for a moment a day working on a computer without Internet connectivity, something of the radical difference between minimal connectivity and full-on broadband enabled connectivity begins to sink in.

One Australian commentator recently observed, in response to a dramatic increase in average per-capita bandwidth consumption/annum, that there are a number of “tipping points” in Internet usage. For example, in the last 18 months, availability of online services as well as wider adoption of home broadband has resulted in a massive expansion of data transfers despite only a marginal increase in average connection speed. Youtube and its ilk have entered a perfect storm of gradually expanding connectivity: it just so happens that at certain points, connectivity results in usage peaks (which then plateau but don’t decline) as consumers discover new ways of using the Internet to interact. This happens with the transition from dialup to always-on Internet, and it happens again at certain speed points–consider tabbed browsing as well as video on demand/what we now consider “bandwidth intensive” activities.

This could be a tipping point for economic development and global integration. Watch closely!