08 Sep 2008

If someone feels called or led or like God spoke to them… no-one knows what to do.

– Mark Driscoll

I actually laughed aloud hearing him say this. It’s really sad but so completely upside down I find it kind of hilarious. Mad world.

26 Aug 2008

This is the one thing that’s totally been annoying me ever since I got this camera. I love it in pretty much every other respect, and, despite enjoying the D80′s top LCD display and extra physical controls (got to use this body for a couple of weeks with work), am still completely convinced it’s the best-value DSLR available today. With the D90 getting official tomorrow, the D80 will probably fall towards the current D60 price point, but still… D60s are the best!

I would’ve been happy with a D40x but there was really no price difference between the two, so whatever.

Anyway: pet peeve that I just solved. File numbering is, by default, non-sequential for every time you empty the SD card! There was no obvious setting to this effect, but that is because, it turns out, settings are hidden by default.

Using the menu, navigate under Setup Menu to “CSM/Setup menu” and select “Full”.

This will reveal more options. Scroll down to the next page of options and select “File no. sequence” and “On”. Importantly in this area is the “Reset” function for if you actually do want to reset between shoots.

Normally I’d be pretty happy with the default behavior, but having recently been doing large-ish travel stints that involve shooting photos that I was syncing as I went more for security (if the camera/card got damaged) than out of actual necessity. As regular shoots would be over more quickly it’s less of an issue for day-to-day use, but I’m lots happier now I know the option’s there!

21 Aug 2008

I’ve been doing the low-bandwidth mobile thing for the past two months due to travel and had accordingly been reserving judgment JUST IN CASE that had anything at all to do with it. But it really doesn’t. Outlook 2007 is an absolute loser of a product. No other software on my computer is as visibly frustrating or unstable. It’s being used with three POP accounts (all mostly well behaved) and one IMAP store (unmitigated disaster) that work fine with other clients. This shouldn’t be so hard to get right. I don’t like having to use webmail, though at least it’s very good webmail.

These are the sort of niggly problems that make OS X look appealing… Mail.app is integrated with OS search and all that other stuff so nicely. Calendars and Contacts are no longer compellingly better on Outlook than elsewhere. In fact, between Sony Ericsson and Microsoft, various contacts in my phone managed to get junked because of character encoding issues — even when using a language installed on both phone and sync computer.

Email is a freakin’ ancient tech. Why can’t this just be straightforward, Microsoft?

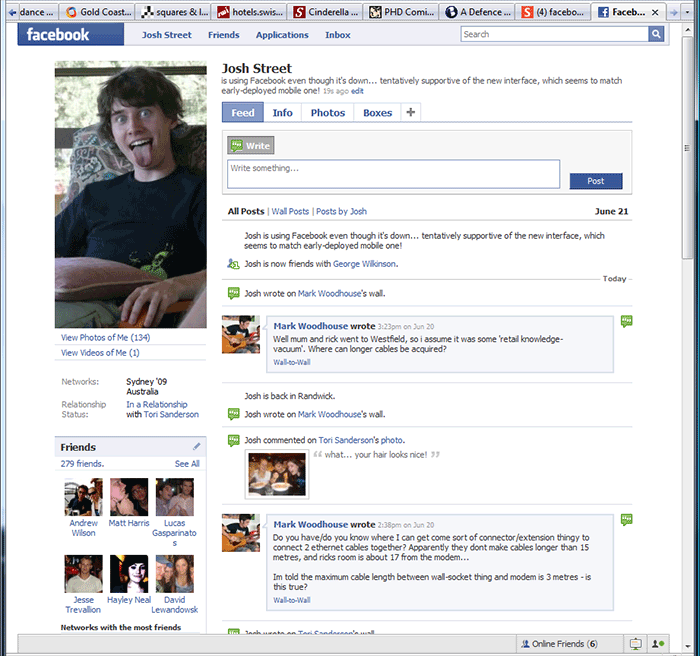

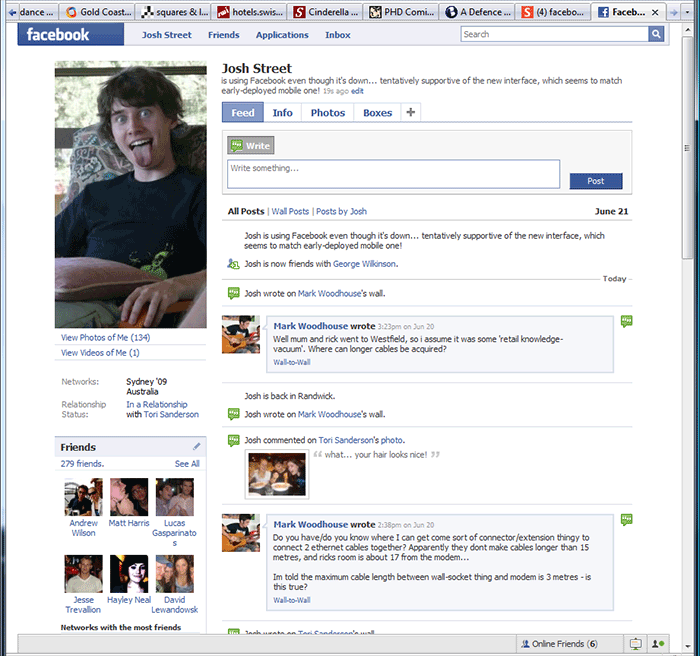

20 Jun 2008

Facebook went out for my user, and after a bit of snooping around I found this…

Coming soon?

17 Jun 2008

A somewhat-long, but generally fascinating paragraph regarding ‘the future’ in the eyes of (particularly) 18th and early-19th century Evangelical moralists and their political counterparts. The “Society for the Suppression of Vice” originated in 1787 with a corresponding piece of legislation and is particularly associated with Wilberforce in the volume quoted here.

Fortune-telling, for example, was one surprisingly salient target. It was one of the social evils identified by the 1802 Society for the Suppression of Vice, and in 1824 the Vagrancy Act made it punishable by a fine or three months imprisonment. Numbers of plebian women and men were prosecuted, on the understanding that their claims to predict the future were a form of fraud or ‘gammoning’ money from the gullible. Other methods of telling the future such as weather prediction, dream visions, and prophecy attracted similar suspicion, indicative of the fact that the ruling classes were coming to see the conceptualization of the future as a matter of great significance. While vulgar millenarian prophets such as Richard Brothers were predicting an imminent time of suffering, leading to redemption, governments were eager to hold out the promise of progress. The future was to be conceived as new and better—fatalism and fecklessness needed to be eradicated. Like the similar conceptual shift in the meaning of the term ‘revolution’ from astronomical return to total transformation, the future was now cut free from the past, notwithstanding the irony that industrial capitalism demanded a considerable degree of forward planning. In suggesting that it was possible to see the future, popular predictive or ‘superstitious’ practices threw an unquantifiable factor into this planning. If indeed the flow of time was not as equable as Newton’s definition had claimed it to be, then the outcomes of scientific experiment, political policy, and technological advance were dangerously uncertain.

from McCalman, I. & Perkins, M. “Popular Cultureâ€. An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age: British Culture 1776-1832. (1999) p.216

The Society were duly attacked in periodicals and all manner of other public forums, as we anticipate they would also be today, for bringing their ‘moralising’ influence to bear upon wider society. But, here at least, the ‘suppression of vice’ does not stem from any overbearingly ‘moral’ source. Certainly, fortune-telling, etc., is decidedly out of step with Abrahamic faith of most flavors (including that of late-18th century Evangelicalism), but the cause given is ostensibly something quite different from that held by these faiths. Particularly, it is on the grounds of fraudulent business conduct that such practices are outlawed. In doing so, there is the tacit acknowledgment that such activities could amount to more than idle entertainment, as most in the West today consider these practices. Yet it is for the preservation of stability, in broader terms, that this probition is made.

In consideration for the ‘future’, we are told, the promise of modernity was held out by censorship.

For what it’s worth, I am against censorship, equally against fortune-telling (considering it either false, accidental, or evil), unconvinced of the necessity of modern-day prophecy but receptive to it insofar as it does not claim that it is, and hesitant to malign Wilberforce, etc. I am also not so much of a modernist as to arrogantly presume the future will bring endless improvement, that people are good, or that humanity at this moment in history is at it’s peak.

All of which leaves me in something of a pickle making sense of this particular episode in history. Thoughts?