03 Jun 2005

An insightful opinion piece from CNet News.com, addressing the fallacy that is the apparent resolution of the digital divide. Something we haven’t seen much of in terms of published research (physical papers, anyway) as of yet is the identification of an emerging technology-literate elite, and that’s something this touches on. If you normally tune out for my posts about this stuff, take a look at this link — it’s fairly succinct, and makes some good points.

02 Jun 2005

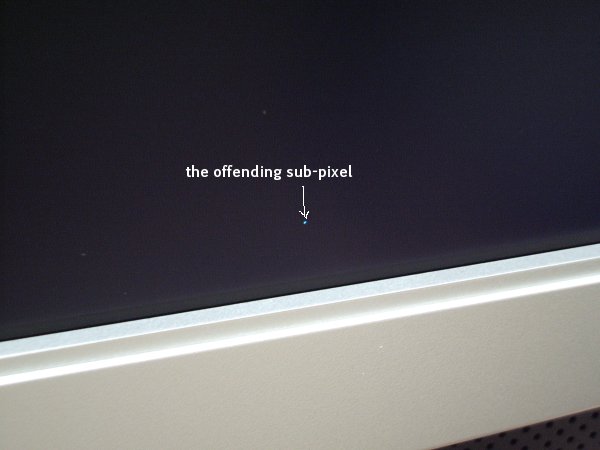

I got my new 17″ LCD today, from one of Michael‘s friends, Byrn. It’s a CMV Polyview V372, which doesn’t inspire images of enormous promotional spending creating a new household name, but, from first impressions, I’m pretty happy with the quality thus far.

It looks something like this, with funky fullscreen visualisations:

Something less obvious in that picture is that it also has two in-built speakers. Most people would advise against using them, and generally I’d agree, but I don’t have any other speakers attached to this computer (Pioneer headphones only), so it’s good for simple system sounds and radio-kinda-quality music. Obviously not pumping bass, but I’ve got the Acoustic Research speakers in my room if I want that, so it’s no big deal.

The monitor sports DVI and VGA inputs (there’s a VGA-only model, but the DVI models all come with analogue input as well), and a native resolution of 1280*1024. They also have an 8ms response time, which would be important to me if I played games, but… well… I don’t. The 14ms version was cheaper, but not enough so to make me want to save the money (there was only $20 in it).

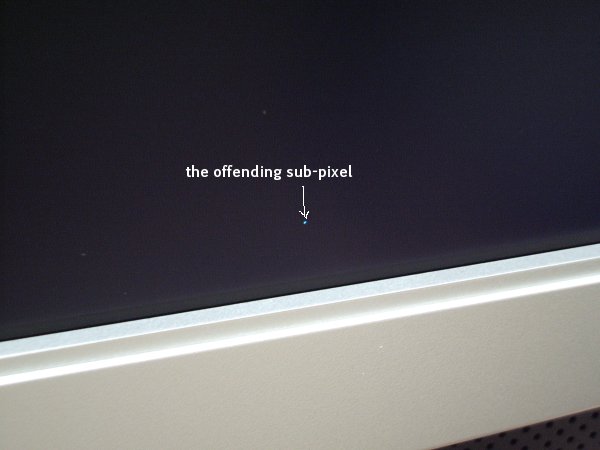

Being an LCD, there’s the inherent risk of stuck-on or stuck-off pixels and subpixels… so that was one of the first things I checked. I only found one stuck pixel, which is stuck-on (that’s more obvious than stuck off) – but it’s only a subpixel, and it’s towards the very bottom of the screen – I didn’t notice until I pulled up a fullscreen black image.

For comparison, there’s a spec of dust above the text (erm… there on purpose, yes… okay, so I couldn’t be bothered to clean it). No big deal.

I’m glad there weren’t more, though, because Polyview’s replacement policy doesn’t kick in until 7 dead pixels according to some websites. It’s also good it’s on the side of the screen, rather than dead centre. My old CRT (now sitting on the floor – I might whack a second graphics card in and try dual monitors when I get time, but probably not) had a burnt-in semi-colon in the middle of the screen, so I knew what having somethind dead-centre could be like. It’s not too much of a distraction, but hardly desirable.

In a bizarre usability bug, the contrast slider is actually setup the wrong way around. Zero is what would normally be 100, and 100 is zero. This would be not-too-weird, but for the fact that the brightness slider is setup “normally”. Go figure. So it took me a little longer to get the picture I wanted than perhaps it should have! I was a little worried the display completely sucked for a few minutes there, but, fortunately, it doesn’t.

When I actually started using it for day-to-day stuff, the thing I was most impressed with was actually a terminal display! This sounds stupid, but I use xterm (no bloat… what can I say!), which has stupidly tiny font sizes. I’m sure there’s a way to change this in software, but I hadn’t found it, and, with this display, I honestly don’t think I need to!

It’s not just the extra size, but the crispness of display in general – it’s great. Speaking of crispness, the interface of this thing has another odd quirk – you can adjust “sharpness” in the menu. Set this to 5 straight away, because it appears just to be blurring pixels into each other. Some would call it anti-aliasing, but really, this should be handled at a software level (and usually is) – the monitor just makes things look like crap.

Overall, it’s a pretty nice display, with a few rather sad interface flaws, but no serious problems.

02 Jun 2005

As a user, the WordPress administration panel Upload facility always frustrated me. It was useful, and quicker to use than FTP in most cases, but the paths it generated for images automatically always needed to be edited before use.

This was, primarily, my own fault – but I’d set things up that way based on the advice of the WordPress administration panel. On the Miscellaneous Options page (/wp-admin/options-misc.php in a typical setup), it proposes two “recommended” paths for both the Destination directory and the URI of this directory, typically your WordPress installation’s wp-content folder and its corresponding absolute URI.

This is simply manipulated into a new string when files are uploaded to generate a tag you can copy and paste into a post – a realisation that should have hit me long ago.

On this site, for example, the recommended URI string is “http://www.joahua.com/blog/wp-content” – note the lack of trailing slash and absolute nature of the path. I only just realised that this was the basis of the string, and so got rid of my trailing slash (I insist on having such things!) and trimmed off the “http://www.joahua.com” – this means the Upload-generated tag now gives a relative URI. No more chopping and changing the generated tags for me!

01 Jun 2005

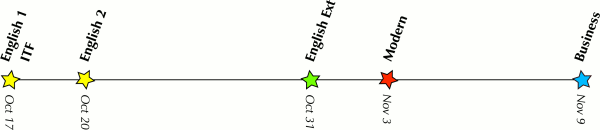

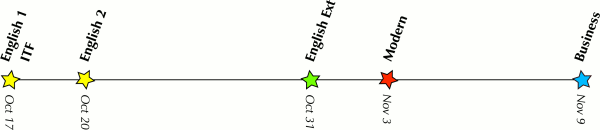

I’ve “stickied” this post because

lots of people a handful of relatives and friends wanted to know what I had when.

My HSC timetable

|

Course

|

Exam

|

Date

|

Time

|

English (Advanced)

|

Paper 1: Area of Study

|

17/10/2005

|

9:20

|

Information Technology Examination

|

Information Technology Written Examination

|

17/10/2005

|

13:55

|

English (Advanced)

|

Paper 2: Modules

|

20/10/2005

|

9:25

|

English Extension 1

|

Written Examination

|

31/10/2005

|

9:25

|

Modern History

|

Written Examination

|

3/11/2005

|

9:25

|

Business Studies

|

Written Examination

|

9/11/2005

|

9:25

|

01 Jun 2005

This is a simple WordPress plugin that allows you to copy and paste from word-processing software that automagically does smart quotes conversion (curly quotes). You can do this without using this plugin – but the characters aren’t proper HTML entities and it’s dirty. CurlyEnc converts curly quote characters to their proper HTML entity codes – something WordPress does perfectly fine with normal quotation marks, but not with these ones.

Simply upload CurlyEnc into your plugins directory and enable it from the Plugins section of your WordPress administration panel, and it should* work.

- No guarantees, no promises. If your weblog sprouts furry ears and starts chasing your mouse, so to speak, I accept no responsibility. Yada yada. Happy to try and help. More seriously, I don’t know that much about character encoding, so I wouldn’t be entirely surprised if my magical character is something of a dud on some installations. I know it’s a good concept, and this is my best implementation of it – if anyone else has a better idea as to how it should be done, please share!

On a related note, it’s released under the GNU GPL — you can have that five lines of code for free! Sorry, no steak knives.

View the PHP source, or download a plain text version.