31 May 2005

Or, how to end a content-drought. It seemed fitting that content should come from one of the things that has distracted me from producing content here!

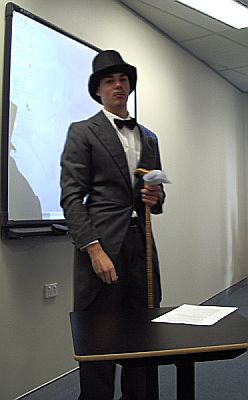

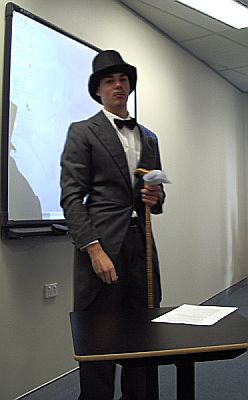

Two people (Alex M and Dean) bothered to get dressed up for today’s festivi… err… assessment, pictured here for your amusement… or their humiliation… or something.

Theoretically, this is an academically focussed class, although some would have us think otherwise. A video, featuring Alex M and Marcelo, (2.1MB, WMV format) for your amusement. It quickly dissolved into… something else!

Sorry Mac (or Linux!) users, no other formats at this time, until I can figure out how to compress Xvid well enough (at best, slightly more than twice the size of the WMV).

30 May 2005

At least one of these has to work okay with the school’s technology…

Native OpenOffice

MS Powerpoint

Macromedia Flash

Adobe PDF

Josh really really really hopes fonts embedding works properly

Aaaannnddd the Flash version worked great, fonts and all! Thankyou, OpenOffice!

Fulltext of the presentation, with slide cues, as promised. PDF, filesize: stupidly large (280KB). Don’t know what happened there!

As for the content of the thing, no jokes are required about me being unable to write an essay/speech without reference to accessibility! It’s purely incidental, I promise! On a slightly more serious note, if some of the sentences utterly suck, chances are I didn’t speak them that way… my paper version had a few pencilled-in corrections, and then there was the inevitable “read but speak differently” factor. The end.

Read on for a HTML version of the same.

Seminar Presentation

Conveying an understanding of the nineteenth century world, and the way in which composers have sought to comment on the institutions and values of the period through critical and creative works.

The nineteenth century world, as presented by various authors of that time, was a period of questionable and oppressive values, in which the individual was significantly burdened by the expectations placed upon them by society. One of the more insightful models developed to explore or explain the presence of values considered to be oppressive or otherwise inequitable in nineteenth century society was the notion of a “compact majority”, devised by playwright and poet, Henrik Ibsen.

Ibsen argued that, within society, there exists two key groups. In this model, the group generally identified as the proletariat is referred to instead as the “compact majority” – that is, the value accepting group. This “compact majority” is seen to accept the dictat of the value-generating/value-electing group – that is, “the establishment”, which is comprised of various influences, including political bodies, religious groups, and educational institutions – all of whom are responsible for creating and disseminating values. These are the two key groups within society, although Ibsen suggests that there is another still. He terms them “fighters at the outposts” – this group rejects the values imposed upon them by society, or, at the very least, is seen to challenge them.

In Ibsen’s own works, we see key figures such as Nora and Dr. Stockmann, as well as supporting characters, such as Captain Horster and Petra, portrayed as these “fighters at the outposts”. The manner in which Ibsen critiques society is consistent with this model, which itself invites further discussion.

Ibsen’s criticism of “society” here is confined to a particular aspect of the same. Perhaps inadvertently, he excuses the “compact majority” and, on the charge of social injustice, instead foregrounds the value-electing group as sole perpetrators – they appear to be offered in appeasement, a propitiation for the crimes of society as a whole. Consistently, it is those with power depicted as being guilty of committing crimes against the individual in nineteenth century society – and this is not confined solely to the works of Ibsen.

Whilst discussing Ibsen, however, it is worth noting that this concept of the powerful oppressing the individual does not function in a pseudo-Marxist political framework – quite the opposite. In Act Four (IV) of Ibsen’s play, An Enemy of the People, Dr. Stockmann declares that “The minority is always right.” He is speaking of the fighters at the outposts. For him, the resistance shall always be a minority movement – the masses are controlled by the value-electors, who, strangely enough, “approve of the very truths that the fighters at the outposts held to in the days of our grandfathers.” Placing aside all argument regarding the apparent futility of their cause in light of this extreme relativism, it is clear that Ibsen holds the establishment-opposing minority of “the outposts” to be correct.

A recurring feature of texts studied and considered to be the canonical works of the nineteenth century is this lucid critique, obviously directed not at any “common” people, but at the value-setting classes and bodies. For this reason, Ibsen’s model is rather insightful, especially given that he did not have our present benefit of hindsight.

Ibsen’s rather explicit identification with an elite minority is something other authors and playwrights of the period perhaps do not as candidly express, although analysis of their works would suggest that many of Ibsen’s peers agreed with him in this. A commonly heard criticism from this class is that the writing styles employed by authors – especially Henry James – of 19th century literature are long-winded and overly conversational in nature. Ibsen is spared this criticism as a small mercy of translation, and James has the defence of his deliberate speech when dictating his works to a scribe – both these aside, the ‘accessibility’ of these works has often been criticised – and not without reason.

“Shakespeare was written for the masses.” This notion is indoctrinated into students throughout high school, to the point where it is possible to make the assumption that any archaic language in canonical works was once perfectly intelligible to the common people. Needless to say, it wasn’t.

Even Henry James’ peer and friend, Edith Wharton, has expressed difficulty in comprehending James’ languid style, however, of greater importance is the accessibility of the text to the common people. Regardless as to the message within a text, this must be encoded in a form the target audience is capable of understanding. A Marxist criticism of literature is quite applicable here – without a doubt, much of this literature we now see to have had an impact in the nineteenth century was inaccessible, employing a lexicon beyond that of much of the population. Composers have sought to comment on the institutions and values of the period not through a blatant and “accessible” appeal to the common people, but in another way.

Both James and Wharton are somewhat self-critical in their writings, in the sense that both belong to the aristocratic element of society that they sought to criticise. Wharton’s The House of Mirth, although written in 1905, may be viewed a product of the century prior in terms of the values it criticises. Whilst contemporary sensitivities may cause us to reject the notion that such criticisms are timeless, there is an element of truth in such a proposition; certainly, society had not seen that much change between the previous century and 1905. Both works critique the indolent nature of these classes, as well as the nature of relationships and the influence of wealth upon these.

Notably, social criticism in both these works is confined to the value-electing group, without allusion to the wrongs of the “compact majority”. This is consistent with Ibsen’s criticism of society – the “compact majority” are largely ignored, the group of lesser consequence in the scheme of things, for if social issues are to be resolved this must, apparently, be achieved from above.

The texts examined thus far all contain characters of greater wealth and status than perhaps would be considered representative of the typical person in this period – perhaps this is justification for the focus on the ills of the value-setters?

Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles is set in the imagined county of Wessex – the purpose of this “imagined” county being to capture the cultural atmosphere of the English countryside, prior to the impact of the Industrial Revolution. From the location alone, Hardy has refrained from a direct critique of the members of a moneyed aristocracy, and yet, by the end of this novel, the nature of criticism is perfectly clear.

Alec d’Urberville is the most explicit figure of such aristocracy in this text, portrayed as having come into money, and acquiring the all-but-forgotten name of d’Urberville – one of many aspects of this text foreshadowing the demise of Hardy’s protagonist. As an object of criticism, Alec is mostly left alone for the earlier parts of the book – following his rape of Tess, Alec quietly disappears, as more poignant criticisms of society are elucidated by Hardy, in the development and subsequent fall of the relationship between Angel and Tess – Hardy criticises the institution of marriage, and, through this, the oppression of women in society. Tess is portrayed as being unable to survive alone. Alec d’Urberville is brought back into the flow of the text, first with Hardy’s masterful use of irony, in a form that criticises the notion of forgiveness within Christianity, and highlights the hypocrisy of the institution of the church itself, and subsequently, most importantly, to make Tess dependent upon him, as she struggles to escape from poverty at Flintcomb Ash whilst still attempting to support her mother and siblings.

As with Ibsen, the criticisms in this text are primarily directed at the institutions of the nineteenth century, rather than at the common people. Tess is presented as being blameless, and the faults of her father and the other occupants of her birthplace are depicted with far greater compassion than Hardy’s portrayal of the hypocritical and flawed nature of society’s value-setting institutions.

So what are these “value-setting institutions”? Some have already been defined. The governing bodies, the church, educational institutions. But there are other groups beside these, less often subjected to criticism. Poet and translator Augusta Webster satirically writes in her poem A Castaway of how “worthy men… think all’s done” if the people can just be made to listen – satirical not because the people refuse to hear, but because their listening serves to resolve little. The speaker in Webster’s poem is a prostitute, who declares herself modest, launching into a criticism of all professions – lawyers, preachers, doctors, journalists, tradesmen…

This sort of blanket criticism is easy to disregard, however, other texts are seen to support such a viewpoint, though their expression is less explicit. The question at this point is how does one define this ‘blanket’ group? In Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People, the protagonist attempts to warn the community of a danger in their midst, and is ostracised for it. It is clear to the reader that the community will eventually fall prey to the contamination, and in this way Ibsen passes judgement on another institution – that of the “community”.

It is this notion of community, sacred in Victorian thought, that is seen to oppress the individual. This “community” is comprised primarily of the value-accepting “compact majority” who are seen to enforce the values of the establishment. The way in which composers have sought to comment on this is two-fold, with some electing to criticise the value-setting classes alone, in an attempt to instigate change from above, whilst other authors, such as Ibsen and Webster, instead launch their critique at the masses, who, by their passivity and acceptance of values, are seen to be in conflict with the individual.

The values of the period, as well as the institutions responsible for dissemination of these, have been commented on and criticised by composers in a variety of ways. The nature of this comment is seen to depend on the author’s own background, and, through exploring this, a greater understanding of the nineteenth century world is developed.

28 May 2005

A critical essay: How do nineteenth century composers bring the plight of the individual to the consciousness of their responders?

Because I haven’t got time to come up with content solely for this website at the minute. 1645 words.

Nineteenth century composers bring the plight of the individual to the responder’s awareness through their portrayal of such characters in a way that appeals to the responder either through the use of empathy, or, in the case of other works, through the use of a rising/falling conflict model in conjunction with elucidatory dialogue to elicit a response from the responder.

Henrik Ibsen’s play Ghosts uses the latter model, making use of clever expositions presented by character in order to force readers to question the society in which they find themselves, and their roles as individuals within that framework. An encompassing work, Ghosts has been criticised as being “a little bare, hard, austereâ€, in which Ibsen has conformed too much to the prosaic ideal and stifled his poetic nature – and, in this, become an author who “cares more for ideas and doctrine than for human beings.†Ironically, it is this portrayal of such ideas and doctrine that, for many, makes this work one of overwhelming humanity.

The model employed by Ibsen here renders characterisation superfluous – his characters are not bound to a single person, to a single individual, but are seen to represent any number of people individually within humanity. Having said this, Ibsen’s works do not generally support the notion of a universal common humanity in which beliefs are shared, drawing a distinction between the “outpostsâ€, the ruling classes, and the “compact majority†– and there is no reason to suppose he deviates from this understanding in Ghosts.

Rather than being a character-driven book, in which empathy is used to endear a protagonist to the responder, Ibsen’s characters are somewhat flat and undeveloped, although in their behaviours, established through dialogue and stage directions, as well as their interactions, they are portrayed as being in conflict. Pastor Manders embodies the oppressive, hypocritical nature of religion – he is more concerned for the appeasement of those who would criticise his lack of faith than he is for the practicality of insurance – a practicality he recognises, but advises against for “the attacks that would assuredly be made upon me in certain papers and periodicalsâ€.

The gullibility of this character with regard to Jacob Engstrand’s nature is not simply that, but rather a reflection of the blindness of religion to many aspects of individual natures within society as a whole – Ibsen comments on the irrelevance of religion in the limited characterisation of Manders, and then further delineates this irrelevance through the conflict introduced between various characters and this figure.

Yet Manders is not simply the representative of the church. Within Ibsen’s model of society, Manders wields a ruling influence from which the “compact majority†draw their values and belief systems. The critique is not only one of the religious establishment, but is inclusive of the state and legal systems – something reflected in the injustices portrayed in A Doll’s House. The accusation levied against such institutions is one of aloofness – Ibsen proposes such institutions are distant from the individual, and cannot adequately comprehend their needs. The epitome of this is his support of euthanasia in the closing scene of the play – a something wholly unacceptable within that society, and similarly open to question in this age. Ibsen argues in favour of this, the closing scene of the play being emotive in its stark nature and eloquent stage directions. The work concludes almost poetically, with Oswald mindlessly repeating a phrase, as his mother, Mrs. Alving, grows hysterical at what he has asked her to do – and the responder can empathise with both figures, neither of which have been understood by the establishment. In establishing such a dichotomy between the state and the individual, the plight of the individual in a collective sense – that is, humanity as a collection of individuals – is brought to the consciousness of the responder.

Empathy is limited as a result of (deliberately) restricted characterisation, but Ibsen’s purpose is still achieved in this work, though perhaps without the nuance of his other works. An Enemy of the People, also by Ibsen, draws a distinction not between the state and the individual, but rather between those on the “outposts†and the common people. It is not, however, solely a work of philosophical self-gratification.

In this instance, the denunciation is instead of the failure of society as a whole to hear any message contradictory to its desires, irrespective of what evils this may require, and similarly without regard for the sustainability of such a stance. The pollution, Dr. Thomas Stockmann argues, is not simply of the baths, but of society. He declares at a public meeting that he has discovered “all the sources of our moral life are poisoned and that the whole fabric of our civic community is founded on the pestiferous soil of falsehood.â€

Such blatancy is not wholly uncharacteristic of Ibsen, his career being one of the more controversial of the great nineteenth century playwrights – undoubtedly also as a result of his popularity. Yet the point remains as an ostracised individual shouts his disillusionment and chagrin with society in this play, a point common to each of his five prose plays, composed from 1877, and termed by Ibsen the “drama of ideasâ€.

The context in which it was written must also be considered, quite apart from the period in time in which these works were composed. Ibsen’s plays were performed to audiences all across Europe, and resistance to these works varied from active censorship in Prussia (unified Germany) and England, to passive censorship – the play was eighteen months old before a theatre agreed to produce it – to public and media criticism. Ibsen’s plays attacked many aspects of the establishment, and, by his own acknowledgement, point to nihilism as an inherent human condition for many people, leading to their turmoil during the play, and subsequent social demise (or, more optimistically, their emancipation) at its conclusion.

France was perhaps one of the more liberal nations in Europe at this time, with the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century perhaps having the most effect upon their state. The subsequent revolutions that had swept across France had created a pervasive progressive mood, but there remained a societal structure rather in accordance with Ibsen’s portrayal of it, albeit with the addition of a middle class supportive of more liberal ideals. This notion of ‘class’ was, for many of the French people, a remnant of a time past which numerous revolutions had failed to abolish – or, more accurately, class distinctions. Artists such as Gustave Courbet criticised this continuing societal rift towards the middle of the century, through the portrayal of alms-giving. His work was not unique in this theme, with other artists such as Bonvin and Pils creating works depicting the same action in the same year, but Courbet’s The Village Maidens Giving Alms to a Guardian of Cattle (or The Village Maidens, 1852.) is unique in the manner it portrays such an act. The work is “an unvarnished, enormous and most unwelcome reminder of class distinctions in the provinces – a reminder that all was not smiling peasantry and reassuring folklore in Franche-Comté, but that there too, the petty bourgeoisie was setting itself apart from the, now threatening, proletariat – and furthermore, with the artist’s own sisters, clad in contemporary bonnets and dresses, rather than regional folk costume, playing the role of moneyed beneficience.â€1 This was, for the middle-classes of Paris, a rather unwelcome reflection of themselves that they sought to avoid recognition of.

The theme of such charity is continued in another of Courbet’s works, Beggar’s Alms (1868), which portrays a beggar granting a young boy a coin – significant, relative to the beggar’s means. The plight of the individual in both these works is portrayed as being of little consequence in an uncaring society – the poor are required to care for the poor, as an indifferent bourgeoisie continues life unburdened.

Burdening of the individual is another theme common to many works of the nineteenth century critical of society, a key example of this being Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles. The protagonist of this text, Tess Durbeyfield (or d’Urberville), bears the sin of a man who goes on unhindered by his act, unaware of its consequence, until he again meets Tess some years later, leading to his demise. Her marriage to Angel Clare is an unqualified failure, despite her continuing devotion to him until, finally, under the weight of her desperation, hope of his return elapses and she is compelled to reside with Alec d’Urberville in order to support her mother and siblings.

Without a husband, Tess d’Urberville is ‘incomplete’ – she is incapable, in the society in which she finds herself, of living independently, as a result of the expectations placed upon her. Society has caused this circumstance through the patriarchal expectation of ‘purity’ falling solely upon a woman with no means of recourse – Alec d’Urberville may be viewed as a motif of oppression rather than an actual character, as his persona is developed by its elements, rather than explicit characterisation. Conversely, Angel Clare is extensively developed so he is endeared in the mind of the responder, such that he exists as an individual as does Tess – his individual actions being guided by his own failure to meet society’s expectations (his lack of religious convictions), but he remains in conflict with this as he leaves Tess whom it is quite clear he loves from his unconscious actions on the first night of their marriage.

Ultimately, Hardy’s protagonist’s plight is the tragic consequence of a sin against her held by society to be a fault of her own. The responder is brought to value the protagonist as an individual in such a conflict through Hardy’s endearing portrayal of her in accordance with the first model outlined at the beginning of this critical essay, and it is thus that an awareness of her plight is raised.

1 Nochlin, L. Realism. Penguin, 1971. Page 124.

28 May 2005

An essay, examining the nature of the nineteenth century, and identifying (some) shaping influences pertaining to this. 1142 words

The nineteenth century was a period of comparative oppression when juxtaposed against today’s more liberal society, especially in terms of societal expectations of behaviour. This encompasses gender roles, political viewpoints, opinions of established institutions, and the acceptance of societal hierarchy, amongst other things.

Gender roles fell increasingly under scrutiny towards the end of the nineteenth century, as authors became more and more open in their criticism of the plight of the individual in society, particularly in terms of the requisite adherence to established roles within the home. A ruling class dominated by male figures demonstrated little regard for the autonomy of females within society; this was reflected both explicitly, in the form of policy enshrined in the legal system of the time, as is evident in the plight of Nora in A Doll’s House, and implicitly, as is demonstrated by Thomas Hardy in the character of Tess in Tess of the d’Urbervilles as she lives apart from her husband at his request.

The notion of gender equality was a prevailing concern of both these works, which may, perhaps, be considered iconoclastic to the concerns of the society that they were published in. Both are, amongst many other works, ‘guilty’ of bringing to light the hypocrisy of the period in its treatment of women, particularly – although this is not their sole concern. Hardy’s work, from its very subtitle (“A Pure Womanâ€), criticises a society in which a protagonist is made to bear the consequences of a sin against her, whilst the offender, Alec d’Urberville, can go on to achieve a (short-lived) salvation which Tess herself rejects in her blind devotion to her husband. In this society, authors argued, a person’s inherent nature was inconsequential in the face of prejudice and societal expectations forced upon people.

The only way such requirements could be circumvented, as portrayed in literature of the period, was through sufficient status created by wealth – something reflected in Henry James’ The Portrait of a Lady, in which Mrs. Touchett claims “You can do a great many things if you’re rich which would be severely criticized if you were poor,†which is similarly echoed in sentiment albeit not as explicitly, in Hardy’s Far From the Maddening Crowd, in which his protagonist rules over an estate even when she is unmarried in a notably assertive manner. She is, to an extent, androgynous in nature; this character is portrayed as having typically ‘masculine’ qualities, whilst Hardy actively develops her feminine nature – Bethsheba’s attraction of no fewer than three suitors, and particularly her flirtations with Boldwood, all serve to reinforce this in face of her assertive qualities. The proposition that a woman was capable of such leadership would generally be rejected in the society of the time, but, through granting her an inheritance, her status was assured by economic means.

There is a dual comment in this – the first of which identifies a prevailing inequality in terms of societal expectations, and secondly on the class distinctions which existed within that society. Artists of this period were revolting against the establishment in their work, and not accepting the ‘limitations’ society imposed upon them. Brontë, for example, could never have enjoyed success but for her use of a male pseudonym to publish her works in the earlier part of the 19th century. This observation is made irrespective of the message present in her works – the notable act in this instance is not the content published, but rather the means by which she achieved this. Class distinctions had, to an extent, diminished towards the middle of the 19th century, at least in urban centres – this made works such as Courbet’s The Village Maidens all the more controversial, as they were an unwelcome reminder of continuing class distinctions in provincial France.

Rejection of such limitations was not restricted to the realms of gender inequality and class. As has already been suggested, composers such as Hardy were criticising other aspects of the establishment – and religion was not excluded from this. Tess of the d’Urbervilles was one such text, in which the ‘purity’ of a woman was based on something outside of her control, and the hypocrisy of the pervading religion of the time was exposed in this. Similarly, Ibsen’s play Ghosts comments on a wide range of perceived societal problems, commenting also on religious hypocrisy through Pastor Manders’ concerns of social perception, and extending so far as to propose euthanasia as right, much to the chagrin of audiences.

Such overt criticisms may be attributed to new scientific observations, such as Darwin’s theory of evolution halfway through the century, and the philosophy of the late Enlightenment (specifically the writings of Kant and Rousseau) bore heavy influence upon many of the thinkers of the nineteenth century. Socially, a belief in absolute values dictated by a deity continued to be pervasive, but the artists of the period bore the scepticism of the previous century, instead adopting a belief system based around extreme relativism – and, in the case of some philosophers, a belief system based around the inversion of Judeo/Christian morality, a prominent example being the writings of Nietzsche, whose ideology focussed on the betterment of society through whatever means necessary, rejecting the conventional notion of ‘sin’.

The rise of socialism is also influential on the writings of many European authors, particularly in light of the industrial revolution, which resulted in the emergence of a ‘proletariat’ viewed by observers as the victims of an unregulated marketplace. Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto (extrapolating their theory of ‘scientific socialism’) proposed that social justice could only be brought about by means of a revolution, although this was by no means the only proposed solution. Figures such as John Stuart Mill proposed liberalism as a solution – an enlightened bourgeoisie whose action would reform capitalism to achieve social justice whilst preserving the notion of ownership. Socialism was a pervasive force in the literature of the nineteenth century, and, towards its end, of growing relevance to the general populace.

The literature of the nineteenth century was characterised by the emergence of these new philosophical and political ideologies, as well as the decline of absolute value systems mandated by religious belief systems. Towards the end of the century, individualism was an emergent force, and, as the feminist movement began to gain support, compositions of the period came to reflect that also.

Despite the changes in philosophy seen to have taken place in literary circles, oppression of free expression by artists continued throughout the century – but this is not reflected in the literature created so much as circumstances and correspondence regarding it. The work of more controversial composers such as Henrik Ibsen, Richard Wagner and Émile Zola, amongst others, was all subject to much criticism, as the views communicated in their work, as with that of innumerable other artists, clashed with a society still reluctant to accept their liberated ideals.

26 May 2005

Or maybe just “extended stress”? Either way.

I’ve got a draft due at the end of next week, but ironically I’m not worried about that so much. Of greater concern is the bundle of paper that has, for the past several months, sat relatively dormant atop a speaker in my room. So… umm… the glue is getting a workout this weekend. Note to self – buy glue.

Haphazard organisation is permitted, perhaps even encouraged – insert some rubbish about reflecting creativity here. I believe in sponteneity and a certain extent of anarchy in composition, but, in my experience, there’s little that can’t be actually coherently documented – in fact, ‘sponteneity’ generally has a catalyst, although our ability to recollect these circumstances will fail. Essentially, I’m going to prepare a document I have little faith in the authenticity of. But that’s okay, provided I do it well, and make it look substantial.

Gaps are creativity. Or something.

As for the draft that is due, I consider that to be more of a process that must be undertaken at some point, rather than anything of inherent importance. Which, it may be added, is something of an inversion of my perspective of some months ago when I first submitted a proposal. Initially, I believed the end product was ultimate, and the process was a necessary evil that must be undertaken to placate markers.

I suppose not that much has changed – I’ve just refined my viewpoints somewhat. The documentation of process is still a necessary evil, but I don’t feel like the end product is so vital. Don’t understand that as my saying “I’m demotivated”… I’m perfectly fine in terms of that.

I now respect process as necessary for the creation of complex ideas, and the shaping of direction from a bunch of (mostly) unrelated threads. Right now, however, I perceive the idea (“perceive” because it may change, of course) to have reached closure. I recognise the plot in its entirety. I could now talk any individual through the story, verbally, albeit perhaps without the same eloquence that may be achieved on paper, sans sponteneity.

Of course, the process of the writing itself refines, but… I don’t mind the idea as is. And that’s what the process is about. Ideas. Not tangible sentences, structure, semantics and implicit post-modernist (contrived) nuance, but concepts. Sometimes, concepts work better than their extrapolated cousins. Not, it must be said, in an underdeveloped way – but simply in terms of power of expression. And confidence.

I think that’s a big part of it, actually. Recognising you have an idea and only you can put it onto paper. That it won’t go anywhere from your mind, unless someone else thinks of it, at which point it ceases to be your idea. The confidence that justice can be done to a notion. Writing something that will be read, and that the author is prepared to have read. That it can be adequately represented — this is my greatest concern.

- a work placement

- new technology at school

- a web development proposal

- weblogs

- cynicism

- influential people/authors of related texts

- other “stuff” I’ve read, influencing style